Platform Cooperativism: A Digital Platform That Opposes Capitalist Monopolies and Promotes the Spirit of Cooperatives.

Digital construction of urban planning as public infrastructure

Imagine it is 2044, and you are still on Earth, having not yet had the opportunity to migrate to another planet. You hold your Tesla Phone, call an Uber-Apple co-branded self-driving car from your home, and meet up with four or five people you arranged to meet on Tinder to dine at a Panda Food restaurant. All these friends have passed the safety screening for exposure history to new infectious diseases. You can pay through an online virtual currency financial system. If more than 30 people book, you can also connect through Spotify to invite a community singer to perform live. Now you don’t even need to touch the screen with your fingers. Elon Musk’s Neuralink technology has passed a series of pig-based tests and received policy support, allowing you to use it with your phone. By agreeing to the service and granting access to your data, you can install it at half price. Meanwhile, China has also launched low-cost neural interface technology phones…

Is this still far from us? Clearly not. In today’s world, where all social networks, the internet, and personal data are seamlessly integrated, smartphones and the applications they carry can meet all the efficiency needs of urban residents, making your daily life—from food, clothing, housing, transportation, education, and entertainment—more convenient. The Uberisation of everything not only brings greater convenience to people’s lives and changes their habits but also transforms the spaces in which we live.

The current sharing economy become a winner takes all game

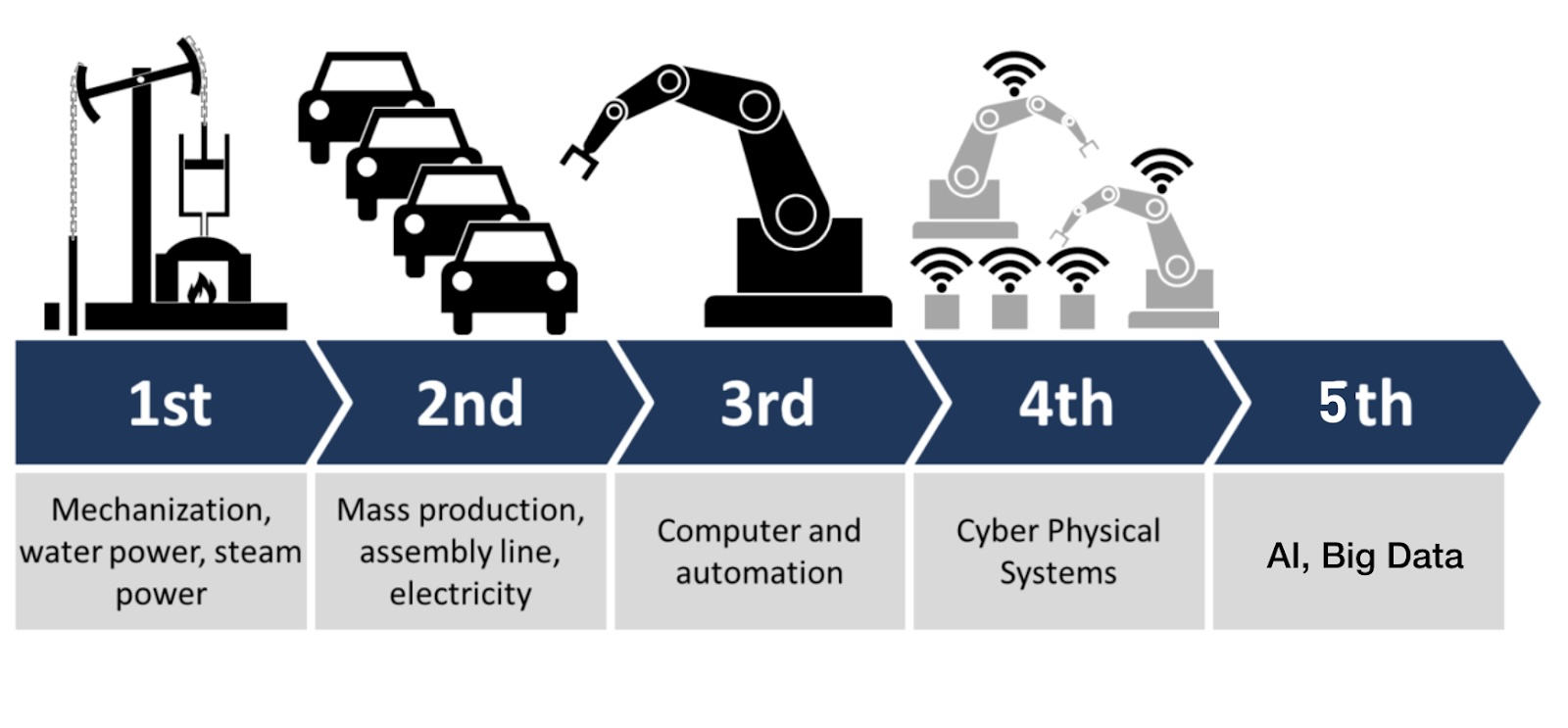

Is the online public space/sexuality still important? On one hand, the issue of widening global income inequality appears more severe than ever. According to the paper ‘The City as a Growth Platform: Helsinki Metropolitan Area Cities’ Response to the Global Digital Economy,’ the authors cite Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s research, which compares Kodak, Instagram, and Facebook to illustrate the trend of increased productivity and growing inequality.

In this context, Kodak represents the ‘first machine age,’ while Instagram and Facebook represent the platform economy, or what Brynjolfsson and McAfee refer to as the ‘second machine age.’ Instagram’s 15 employees created a simple application that attracted 130 million users. Facebook acquired Instagram in 2012 for over $1 billion. At the time, Facebook had approximately 4,600 employees, while Kodak, at its peak in the 1970s, employed up to 140,000 people, with one-third based in Rochester, New York. This comparison highlights the most significant issue: there is a vast disparity in the distribution and dissemination of wealth between the First and Second Machine Ages. Platform companies like Facebook have more customers and greater market value than Kodak, but they employ only a fraction of the workforce that Kodak and similar high-tech companies of the industrial era did.

In summary, over the past two centuries, wages have increased alongside productivity gains, providing a certain legitimacy to the claim that everyone benefits from technological progress. However, recently, median wages have ceased to keep pace with productivity. This decoupling is a key indicator of the nature of the platform economy. It is about households rather than individual workers, or total wealth rather than annual income. As technology advances, many are being left behind. Another snapshot of current developments is the comparison between wages and living costs. For example, from 1990 to 2008, the median household income in the United States increased by approximately 20%, while housing and university costs rose by over 50% and healthcare costs by over 150%. Even in the United States, this trend and many similar trends indicate a polarising trend, as the United States is a country that has absorbed a significant portion of the value created by platform companies.

In ‘The Winner Takes It All,’ author Anand Gurudharadas reveals a concept where these wealthy elites, under the guise of ‘improving social issues,’ prioritise protecting themselves. The rise of this power to solve public problems through ‘private methods’ represents a new private approach to changing the world by elites and leaders, which is superior to the old-fashioned public and democratic methods: in the past, governments independently took responsibility for solving the nation’s most pressing issues, including infrastructure such as road systems and social programmes (such as the New Deal in the United States).

Today’s challenges are more complex and interconnected than ever before, and cannot be resolved through single actions. This presents an opportunity for governments to involve various actors, including non-profit organisations and businesses, in the ‘influence economy.’ This approach elevates funders to a leadership role in addressing public issues, granting them the power to block solutions that threaten their interests. Meanwhile, universities have committed to using ‘entrepreneurship’ as a new focus to address ‘some of the world’s most pressing issues.’

Urban Platformism — Urban policy interventions must consider the city’s own development

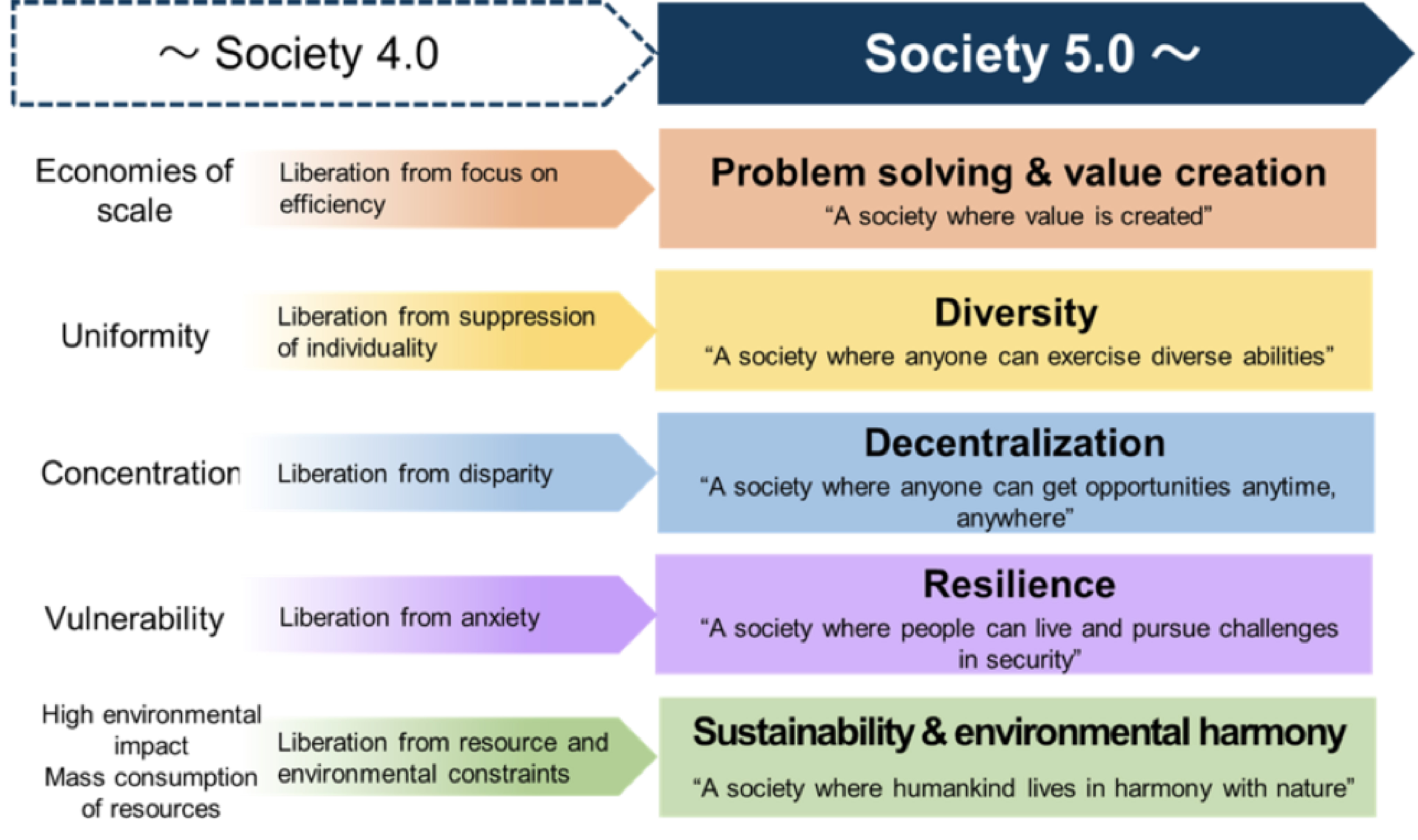

How does the spatial sense of a city change due to the efficiency required by smart cities? What further impacts does this have on residents? According to a description on a Japanese big data website, upon entering Society 5.0, all data accumulated since Society 4.0 will be processed and converted into new intelligent forms through artificial intelligence (AI), then disseminated across all aspects of people’s lives. As people will receive products and services at the appropriate time and in the right quantity, their lives will become more comfortable and stable.

Our assumption is that cities are gradually understanding how the global economy is changing, so they are applying new models and tools to help them adapt to the global digital economy. Some cities have also established local growth platforms aimed at combining the liquidity of the new economy with the ultimate needs of city governments, ultimately guiding beneficiaries to their locations or at least engaging with institutions tied to specific locations.

It appears that, in addition to the previously discussed global context, the fundamental element that must be considered is ‘digitalisation.’ Cities have begun to realise that they need to leverage digital technology to capitalise on the rapidly developing digital-driven economy, which can enhance urban economies through increased productivity of local businesses, global innovation networks, or the adoption of platform models. As an example of platform capitalism, city governments face new challenges related to platform urbanism: communities require sufficient infrastructure to facilitate the operation of the platform economy and the ability to negotiate with private platform companies and local service providers. They clearly benefit from an economic structure where sectors related to the platform economy hold significant influence.

Additionally, local areas require talent, which is crucial for entrepreneurship, R&D, management, and specialised functions within the platform economy. These aspects draw our attention to infrastructure, industry, and talent, which are the fundamental elements for localising platform economy activities, and conversely, the fundamental elements for connecting local and global platform economies.

How techno-feudalism affects urban development

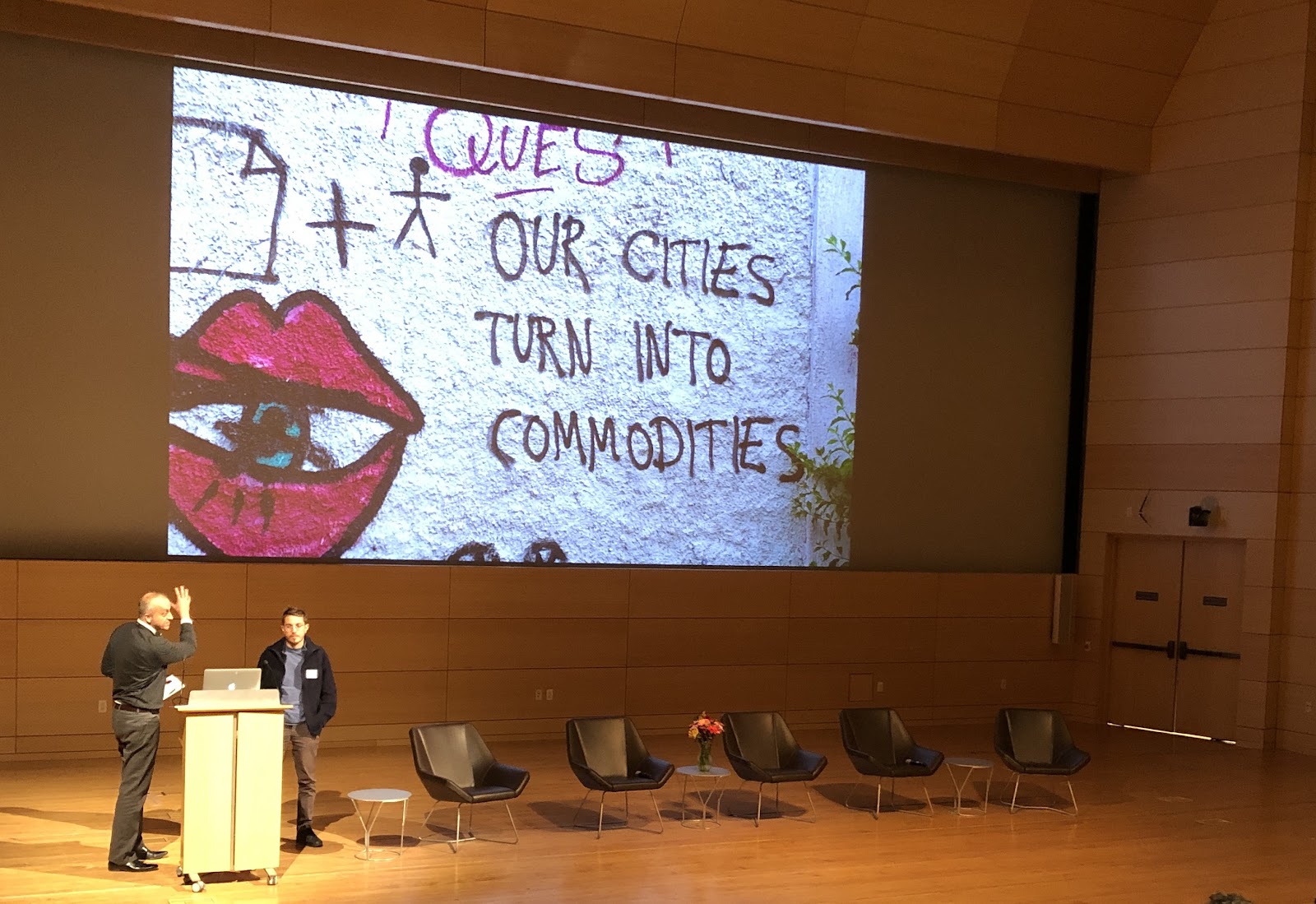

The profits of the global digital economy—requiring a continuously evolving urban growth machine to sustain them. Quoting the report ‘Cities as Growth Platforms’ 7, the discussion of cities as growth engines, the mechanisms and actors driving these engines, is nothing more than an elite game of free-market competition. In this game, actors with shared interests invest resources and organise public and private sector networks to drive economic growth. In this context, communities and people are viewed as potential beneficiaries or, due to different considerations, as individuals who must be sacrificed for the sake of overall growth. Regardless of the outcome, in this elite-led growth game, communities and people are often reduced to passive units. Therefore, urban development often leans toward capital, with various economic zones, public transportation, electricity and water resources, and investment incentives—all of which are public goods belonging to the city—being prioritised as development options, while the profits are exclusively enjoyed by large capital companies.

In the era of the digital platform economy, the face of ‘capital’ has shifted from the chairman on television to the sleek logos and AI customer service chat rooms on the screen. Platforms serve as online intermediaries for social and economic interactions and transactions. The most powerful or effective platforms representing the new economy are digital platforms. These include digital marketplaces and non-essential consumer goods companies such as Amazon, eBay, and Alibaba, special forms of sharing, and supply-demand matching in the service industry, such as Uber and Airbnb, as well as internet and communication companies like Google, Baidu, Facebook, and Tencent, which are at the forefront of the new economy.

Viewing platforms as key integrators and facilitators in the ‘global digital economy,’ they capture the essence of this economy from the perspective of high-tech companies and the mechanisms that drive the development of new economic sectors and bring together key participants. Platforms rely on a decentralised value creation logic to attract users, facilitate their transactions, and profit from them. Additionally, from the perspective of how platforms utilise algorithms and other forms of artificial intelligence to facilitate processes, this business model is clever, especially when combined with massive processing power, enabling exchanges on an unprecedented scale. Such a business model also carries inherent risks, sparking discussions about privacy, power, and regulation in the platform economy.

Increasing Urban Publicness Through Cooperativism in the ‘Platform Generation’

How might urban spaces under platform cooperativism look? How can people truly share what they need? As a radical tradition, labour solidarity avoids alienation through organised structures. How can this tradition respond to the accelerated progressivism of the digital age? Can the technologies applied to startups be combined with the spirit of the cooperative economy to create a more equitable life for people?

Through platform cooperativism, the idea is to use platform technology to connect workers and service providers, with workers autonomously organising cooperatives. How can platform cooperatives contribute to this? Can local services align with new urbanism networks and form alliances as ‘rebel cities’? In the face of mutant fascism, can local lifestyles be reimagined to transcend blood, soil, nation, and corporation, becoming neighbourhood and public?

From 2019 to 2021, the platform cooperativism movement established participatory design and technical toolkits, enabling more local labour groups to gain an understanding of technological tools and engage in cross-regional cooperation, thereby continuing to build successful cases, hacking into the future they desire, and finding the commons in digital space. This simultaneously requires policy support for cooperative regulations and funding. The following are examples of platform cooperativism developed to address urban labour issues.

Fairbnb.coop

Fairbnb’s operational model is based on four core principles: collective ownership, democratic governance, public participation, and institutional accountability. This strategy of empowering citizens effectively strengthens social structures within urban areas and, to some extent, limits gentrification and inequality. Emanuele Dal Carlo and Damiano Avellino introduced their plan at the 2019 Platform Cooperation Conference. Fairbnb.coop was formed in response to the growing issue of over-tourism in Venice affecting local life. They also reflected on their positioning — not merely as a protest against existing platforms, but as a genuine effort to build a platform.

Fairbnb’s operational model is based on four core principles: collective ownership, democratic governance, public participation, and institutional accountability. This strategy of empowering citizens effectively strengthens social structures within urban areas and, to some extent, limits gentrification and inequality. Emanuele Dal Carlo and Damiano Avellino introduced their plan at the 2019 Platform Cooperation Conference. Fairbnb.coop was formed in response to the growing issue of over-tourism in Venice affecting local life. They also reflected on their positioning — not merely as a protest against existing platforms, but as a genuine effort to build a platform.

They believe that to stand firm, both feet must be in sync—resistance is needed, but so is progress. Breaking free from traditional frameworks and constraints, they decided to take the plunge and try it out. The biggest challenge initially was securing funds to sustain the cooperative’s operations. As for how it actually works, the goal is to create a model that benefits both hosts and guests, bringing positive impacts to the entire community. Like other platforms, FAIR BNB charges a 15% fee, half of which supports the cooperative’s operations, and the other half is used by guests to fund local social projects. Thus, both hosts and guests pay the same proportion, while also benefiting the entire community.

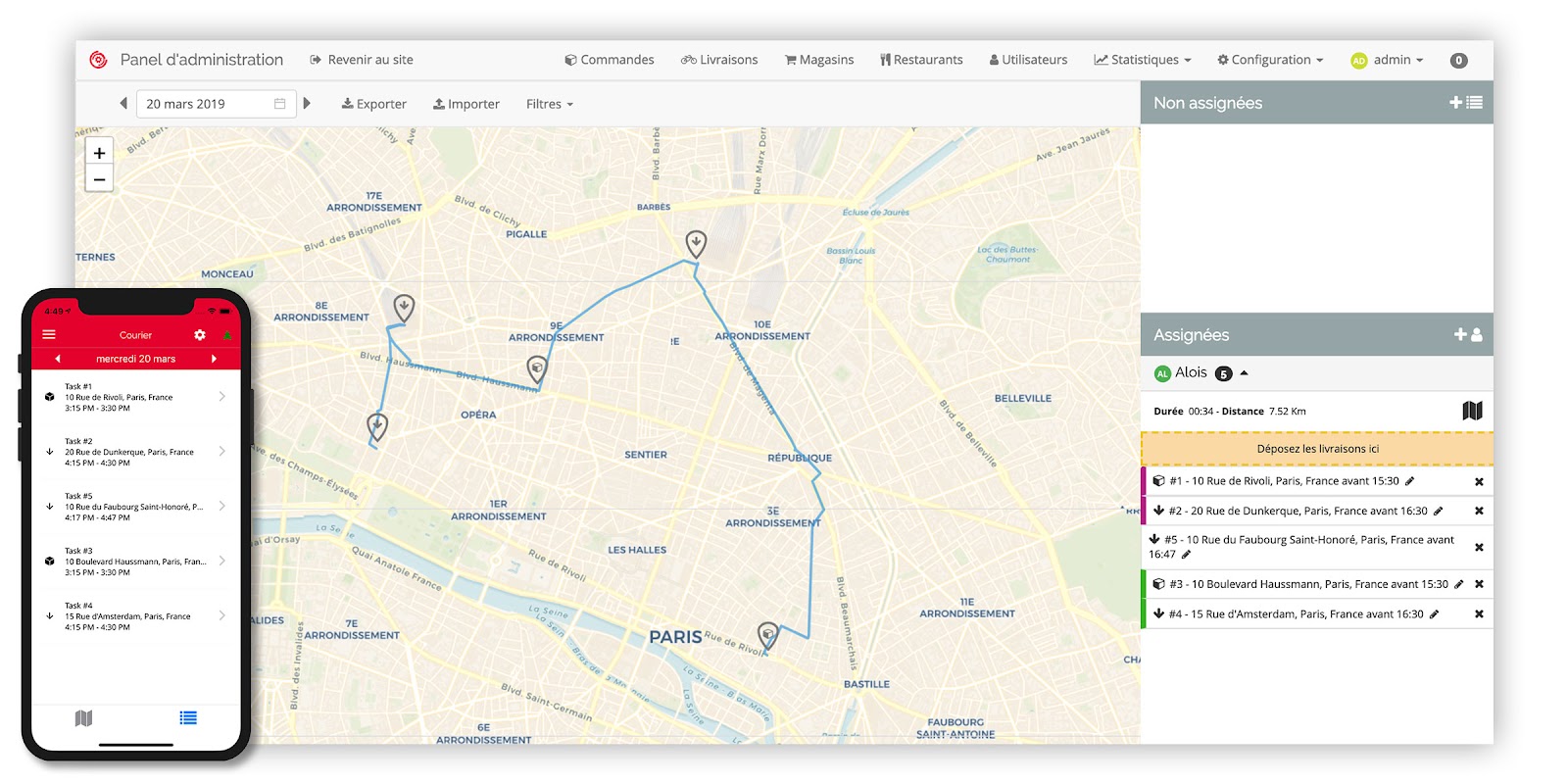

Coop Cycle — Transport Cooperative/Delivery Platform

Coop Cycle was founded in Europe with the aim of creating a bicycle delivery company that truly belongs to local workers, such as this company in Bordeaux. There are also companies like Mensakas, so Coop Cycle is a consortium of several companies. Through the continuous unity of forces in various regions, grassroots activities are strengthened. As of 2019, there are 26 such cooperatives in Europe, employing approximately 100 delivery workers, generating 1.2 million euros in revenue, and securing significant subsidies, thereby demonstrating that these organisations can be localised.

Coop Cycle builds networks to pool resources. This is not a confrontation between local organisations and capitalist platforms, but rather an effort to establish meaningful, global-scale organisations that remain closely connected to grassroots communities. They have created centralised services and shared platform technology. Some cooperatives are not yet well-known, but by bringing everyone together, users can find the services they need on this digital platform.

Contracts and salary management are also crucial. Employees are at the core of all services, so they must be fully protected regardless of the country they are in. Therefore, we must understand how to utilise the laws of European countries to protect every employee. Additionally, there is a technical aspect highly relevant to the delivery industry: business collaboration. For example: bulk purchasing, supporting the establishment of new cooperatives, launching initiatives, etc. So, the main point of this slide is that when the scale expands to the entire European Union, it does indeed bring a certain degree of influence.

Coop Cycle also faces many challenges in its development. The first is to establish a sustainable and democratic business model from the very beginning and maintain it as the scale continues to grow. To be honest, keeping the business model sustainable and democratic is indeed a challenge. Another challenge is how to secure funding. They initially proposed the idea of membership fees, with each local cooperative contributing investment funds. However, the issue was that many organisations were newly established and lacked sufficient funds. Therefore, they applied for two rounds of grants and successfully secured them. At least in Europe, many political partners view this as a social issue, but grants are not a continuous source of funding.

Another important issue is how to provide employees with a productive work environment, especially for those responsible for projects of varying scales, which remains a challenge. Finally, how to prevent capitalist platforms from taking over your project. How can open-source digital platforms compete with capitalist companies? How can we avoid misuse while ensuring the platform remains transparent and accessible to everyone? The solution is a licence. With this licence, the platform remains open, but its commercial use is limited to members of social enterprise cooperatives. Coop Cycle has also made significant efforts to protect public assets.

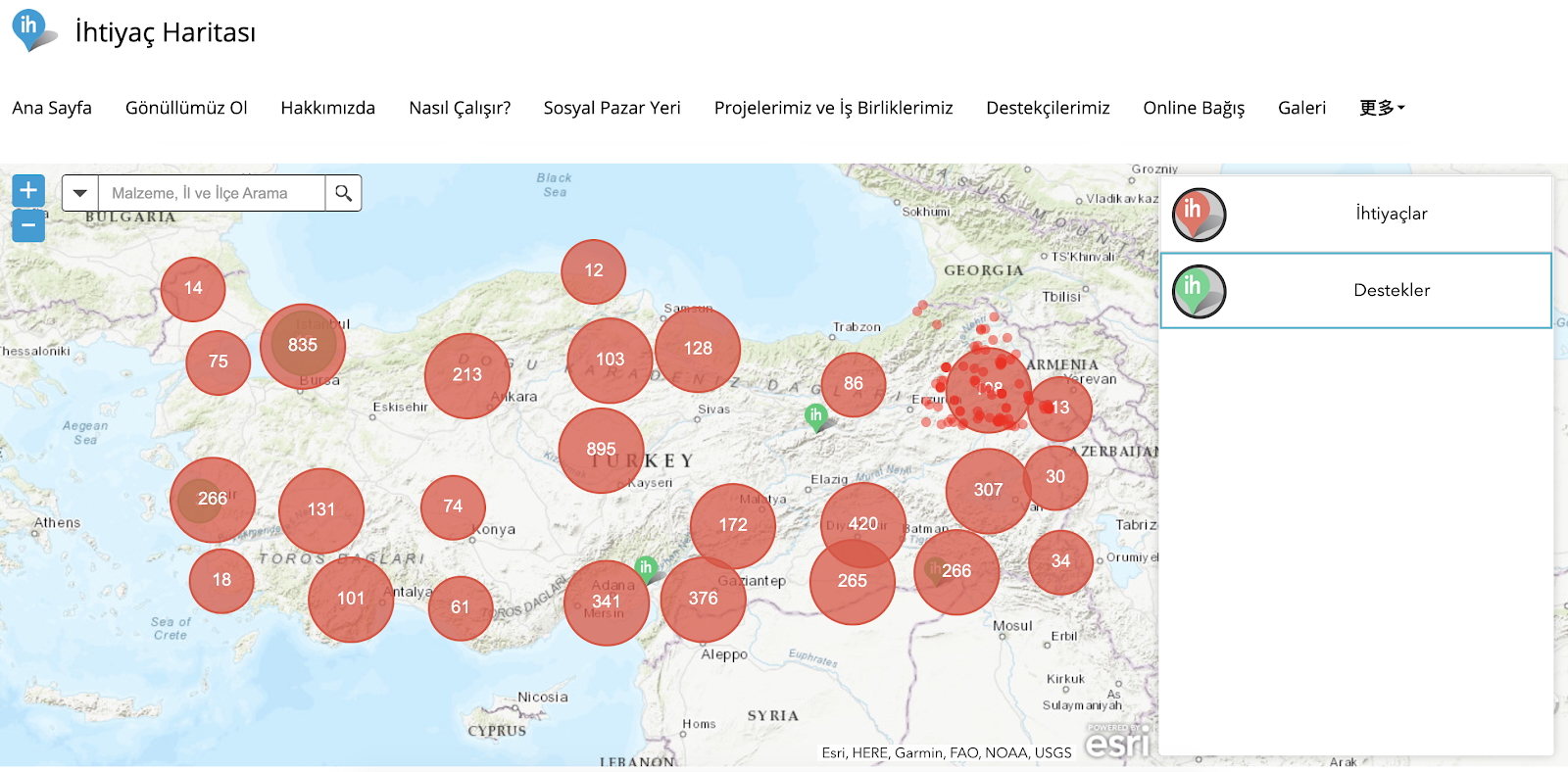

Turkey’s NeedsMap (İhtiyaç Haritası) Demand Matching Map Platform

NeedsMap developed its 2020 strategic plan with the participation of various stakeholders: humanitarian aid, technological response, and economic recovery. The NeedsMap platform is a data-matching map based on actual material distribution, bringing together those in need and those who wish to help. It addresses individuals’ basic needs (such as clothing, shoes, jackets, and blankets) as well as the needs of non-governmental organisations, public schools, cooperatives, volunteer groups, social platforms, and community centres (e.g., volunteer supplies, school supplies, books, even paint, computers, projectors, and office furniture sharing and donations).

One of the main founders, Ali Ercan Özgür, has dedicated his career to researching socio-economic maps and data-driven maps, observing how neighbourhood-based geographic data mapping plays a crucial role for decision-makers, particularly in local governments. In 2012, he established an online platform called City Kid, which documented urban residents’ issues through photos and videos and enabled users to directly share these issues with local authorities. In 2015, a group began considering the use of a web-based application to address map-based digital systems capable of addressing social development needs at the urban and community levels.

Mert Fırat, a renowned Turkish actor and UNDP Turkey Sustainable Development Goals Goodwill Ambassador, also participated in the development process, agreeing to establish a ‘social cooperative’ to meet common needs through a web-based platform. They believed that a cooperative was the most appropriate institutional form, reflecting values centred on solidarity and mutual aid. In October 2015, the beta version of NeedsMap (test version) was launched at the UNDP Social Good Summit and has since evolved into its current form.

This is a network platform where people voluntarily participate, using a non-monetary donation system to address social issues related to poverty. Currently, NeedsMap primarily serves the region of Turkey, with seven main partners, serving over 95,000 users, employing seven full-time staff members, and having raised over 512,000 USD to date.

In addition to the seven founding members who form the board of directors and audit committee, we have four members responsible for different departments (finance, volunteers, online platform, public-private sector relations, project planning, public relations, and transaction operations). Establishing a platform cooperative allows us to collectively address community issues and share decision-making and responsibility.

For NeedsMap, becoming an effective and user-friendly social platform within the circular economy is crucial. They have no warehouses or stores but operate a volunteer-based cooperative platform that can meet the needs of thousands of people. NeedsMap has 10,000 volunteers working in the field, offices, universities, and digital environments.

Conclusion

Taipei ranked 8th in the 2020 IMD Global Smart City Ranking, one position lower than the previous year. But has our city truly become smarter? Or is this ‘smartness’ merely a reference value for investment rankings by a few capital companies? As cities become increasingly homogenised due to competition in network and digital technology, how should we redefine development strategies?

Beyond economically oriented urban planning, how can we develop city resources (science parks, transportation infrastructure, industry-academia collaboration, etc.) that are more conducive to ‘platform economy’ development? How should cities apply data and develop technology, and how can we promote development based on ‘public value ethics’? When facing the onslaught of transnational platform capital companies, must cities always wait for problems to arise before responding with solutions, or can we take the initiative to proactively defend urban data as public infrastructure and encourage more citizen-led collaborative platform economy strategies?

[1] Apple and Google Collaborate on COVID-19 Contact Tracing Technology, 10 April 2020.

[2] Musk demonstrates Neuralink’s bio-electronic brain technology using three pigs, revealing the latest achievements in brain-computer interface technology, 31 August 2020, Digital Times.

[3] Uberisation describes how new entrants use computational platforms (such as mobile applications) to commoditise existing service-based industries, enabling transactions between service customers and providers. The so-called ‘platform economy’ typically refers to bypassing existing intermediaries. Compared to traditional business models, this business model has different operational costs.

[4] City as a Growth Platform: Responses of the Cities of Helsinki Metropolitan Area to the Global Digital Economy, 2020, Urban Sc, Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko, OrcID, Markus Laine, and Henrik Lönnqvist.

[5] Winner Takes All: The Most Profitable Deal in History, The Masked Elite Who Seize the World Through Charity, Linking Press, Anand Girdharad.

[6]The Future of Humanity and the World of Technology — Society 5.0

[7]City as a Growth Platform: Responses of the Cities of Helsinki Metropolitan Area to Global Digital Economy, 2020, Urban Sc, Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko, OrcID, Markus Laine and Henrik Lönnqvist.

[8] What is platform cooperativism (platform coop)? A broad definition of platform cooperatives: ‘Platform cooperatives are collectively owned, democratically managed enterprises that use digital platforms to connect people and assets, enabling them to meet their needs or solve problems.’

References

*Digital democracy? Options for the International Cooperative Alliance to advance Platform Coops,ICA.

*Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities (Geographies of Media),2020,Sarah Barns.

*STIR MAGAZINE

*Fairbnb.coop launches, offering help for social projects.

*Needs Map – İhtiyaç Haritası GLOBAL,INNOVATION EXCHANGE (https://www.globalinnovationexchange.org/innovation/needs-map-ihtiyac-haritasi)

*The Future of Humanity and the World of Technology — Society 5.0

2021-03-29 published on eyes on place

平台合作主義:反資本壟斷並建立合作社精神的數位平台

2021/03/29 文:Yulin Huang

想像現在2044年,身為還在地球尚未有機會移民其他星球的一員,你拿著 Tesla Phone,從你家叫了Uber與Apple聯名的無人車,與Tinder上相約四五個人一起去 Panda Food 的餐廳吃飯,這些朋友都通過了新型的傳染疾病接處史的安全檢測1。支付過程你可以透過線上的虛擬貨幣金融系統,如果超過30人預約的話,還可以透過 Spotify 串接邀請社區歌手現場演出,現在你甚至不必用手指觸滑螢幕了,Elon Musk 的Neuralink2 技術已經通過一系列的豬體測驗,並通過政策支持,提供你搭配手機使用,同意服務獲握你的數據就可以半價安裝,同時中國也推出了低價的神經串連技術手機……

這還離我們很遙遠嗎?顯然並不,在今日所有社交網絡、互聯網與個人數據無縫接軌的狀況下,智慧型手機以及他們上面裝載的應用程式就能滿足都市居民所有提高效率的需求,涵蓋你的一天食衣住行育樂都變得更便利了。萬物優步化3(Uberization)除了對人們帶來更便利的生活,除了改變人們的生活習慣,是否也改造了我們生活的空間?

現今的共享經濟仍是「贏家全拿」的平台資本主義遊戲

網絡公共空間/性仍然重要嗎?一方面,全球貧富差距加劇的問題顯得比過往更為嚴重,根據〈都市作為增長平台:赫爾辛基都會區城市對全球數字經濟的反應〉4中,作者引用Brynjolfsson和McAfee的研究,當將Kodak,Instagram和Facebook進行比較時,說明了生產率的提高和兩極分化的趨勢。

在這個場景中,柯達代表著「第一機器時代」,Instagram和Facebook代表著平台經濟,或者代表了Brynjolfsson和McAfee所說的「第二機器時代」。 Instagram 的15名員工創建了一個簡單的應用程序,吸引了1.3億用戶。 Facebook在2012年以超過10億美元的價格收購了Instagram。當時Facebook擁有約4600名員工,而柯達在1970年代的鼎盛時期擁有多達14萬名員工,其中三分之一在紐約州羅切斯特。這個比較最凸顯出最重要的問題是,在第一和第二機器時代,財富的分佈與傳播之間存在巨大的差異。像Facebook這樣的平台公司比柯達擁有更多的客戶和更大的市場價值,但它們僱用的員工只是柯達和工業時代的類似高科技公司的一小部分。

概括地說,近兩百年來,工資隨著生產率的提高而增加,這提供了某種合法性來宣稱每個人都受益於技術進步。但最近,中位數工資已停止追踪生產率。這種脫鉤是平台經濟性質的重要標誌。家庭而不是個人勞動者,或者總財富而不是年收入。隨著技術的進步,許多人正在落後。當前發展的另一個快照是工資和生活費用之間的比較。例如,從1990年到2008年,美國家庭收入中位數增長了約20%,而住房和大學費用增長了50%以上,醫療保健增長了150%以上。即使在美國,這個趨勢和許多類似的趨勢也顯示出兩極分化的趨勢,美國是一個已經吸收了平台公司所創造的價值的很大一部分的國家。」

在《贏家全拿》5中,作者阿南德‧葛德哈拉德斯揭示了一個概念,這些富裕菁英領導,以「改善社會問題」為名,優先順序卻是尋求保護自己。這種以「私人方法」解決公共問題的勢力崛起,由菁英與領導的新私人改變世界的方法,比老派的公共和民主方法優越:過去的年代,政府獨立負責解決國家最終要的問題,包含如基礎建設等公路系統、社會計畫(如美國新政New Deal)。

今日的挑戰比過去更加複雜和交互關聯,無法藉由單一行為來解決,因此,這是政府讓影響力經濟等眾多行為參與的機會,包含非營利事業與企業。這個方法藉由把出資者提高到領導解決公共問題的地位,賦予他們全力阻止會威脅他們的解決方案。同時,大學承諾以「創業精神」這個新焦點,作為「一些世界最急迫問題」的解決方法。

都市平台主義——都市政策的介入需考量城市本身的發展

都會的空間感,因為智慧城市所要求的效率有什麼樣的變化?對居民有什麼進一步的影響?根據日本大數據網站的描述,進入Society 5.0時,Society 4.0以來的所有數據都將被處理,並通過人工智能(AI)轉換為新的智能形式,並傳播到人們生活的各個領域。由於人們將在適當的時間和正確的時間獲得產品和服務的供應,因此人們的生活將更加舒適和穩定。

Photo Credit:2021 World Economic Forum,https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/modern-society-has-reached-its-limits-society-5-0-will-liberate-us/

我們的假設是,都市正在逐漸了解全球經濟的變化方式,因此應用了新的模型和工具來幫助他們適應全球數字經濟。一些城市還建立了本地增長平台,該平台旨在將新經濟的流動性與市政府的最終需求結合起來,以最終將受益者引導至其所在地或至少與那些和那些與特定地點有聯繫的機構參與者。

看起來,除了先前討論的全球性之外,必須考慮的基本要素是「數位化」。都市已經開始意識到,他們需要利用數位技術來利用迅速發展的數位驅動經濟,這種經濟可以通過提高本地企業的生產率,全球創新網絡或透過採用平台模型來加強城市經濟。作為平台資本主義的一個實例,都市政府面臨與平台城市主義相關的新挑戰:社區需要足夠的基礎設施來促進平台經濟的運營以及與私人平台公司和本地服務提供商進行談判的能力。它們顯然受益於與平台經濟相關的部門具有強大影響力的經濟結構。

此外,地方需要人才,這些人才對於平台經濟的創業,研發,管理和專業功能至關重要。這些方面將我們的注意力引向基礎設施,行業和人才,這是平台經濟活動本地化的基本要素,並且反之亦然,這是將本地與全球平台經濟聯繫起來的基本要素。

全球數位經濟的獲利——需要不斷發展的城市增長機器來支撐

引述「都市作為增長平台」報告7,討論都市作為成長機器的驅動引擎,推動引擎的機制與行動者,無非是透過自由市場競爭的菁英遊戲。在這個遊戲裡具有共同利益的行動者,投入資源、組織公、私部門網絡以帶動經濟成長。這個脈絡下,社區與人民被視為潛在的受益者,或因不同權衡考量下,為整體成長必然得犧牲的個體。無論是哪一個結果,在這個菁英領導的成長遊戲裡,社區與人民常常被簡化為沒有能動性的單位。因此都市的建設往往向資本靠攏,總是被視為優先建設選項的各種經濟園區、公共交通、電力水力資源與投資優惠,都是屬於都市的公共財,獲利卻由大型資本公司所獨享。

在數位平台經濟的時代,「資本」的面貌從電視上的董事長,換成銀幕上設精美的logo與人工智慧客服聊天室。平台可實現社會與經濟互動和交易的在線中介。代表新經濟的最強大或有效的平台是數位平台。其中包括數位市場和如 Amazon 、 eBay 和 Alibaba 之類的非必需消費品公司,特殊形式的共享以及服務行業的供需匹配,例如 Uber 和 Airbnb 以及互聯網和通訊公司,例如Google,百度,在新經濟中走在前列的Facebook和騰訊。

將平台視為「全球數位經濟」中的關鍵集成商和促進機制,它從高科技公司和促進新經濟部門發展並將主要參與者聚集到一起的關鍵機制的角度,抓住了這種經濟的本質。平台依靠分散的價值創造邏輯來吸引用戶並促進其交易並從中獲利。此外,從平台在便利化過程中利用算法和其他形式的人工智能的角度來看,這種商業模型很聰明,再加上巨大的處理能力,以前所未有的規模進行交換。這樣的業務模型也具有固有的風險,引起了有關平台經濟的隱私,權力和法規的討論。

在「平台世代」透過合作主義增加城市公共性

平台合作主義8下的城市空間如何可能?人們如何真正地分享他們所需要的?合作社作為一種激進的傳統,勞工團結避免被異化的組織,在今日如何應對數位時代的加速進步主義?所有應用於新創公司的技術,能否結合合作經濟的精神,為人們創造更公平的生活?

透過平台合作主義,這個想法是透過平台使用技術來連接工人和服務提供商的用戶,工人自主組織合作社,平台合作社如何為此做出貢獻?在地服務是否能跟隨新的城市主義網絡和成為『反叛城市』的聯盟?面對變種法西斯主義,當地的生活形式可以重新想像為超越血液、土壤、國家和公司,成為鄰里、公共?

2019年到2021年,平台合作主義運動透過建立參與式設計與技術工具箱,讓更多在地勞工團體能透過對科技工具的了解與跨地域的合作,持續建立成功的案例,駭進他們想要的未來,找到數位空間的公有地;而這同時需要政策對合作社法規與資金的幫助,以下列舉基於解決城市的勞工問題所發展的平台合作主義案例。

Fairbnb.coop —— 並非只是想針對現有平台的抗議,而是建立自主的合作平台

Fairbnb的運營模式是由:集體所有制、民主治理、公眾參與和制度問責,四個核心原則而生。賦予公民權力的策略,有效加強了城市區域範圍內的社會結構,某種程度上也限制了高價化和不平等現象。伊曼紐爾·達爾·卡洛(Emanuele Dal Carlo)與達米亞諾·阿韋利諾(Damiano Avellino)於2019平台合作年會介紹他們的計劃,Fairbnb.coop 因為有感於威尼斯逐漸因為觀光客過多的問題影響當地生活,而開始組織起來,他們也思考自己的定位——並非只是想針對現有平台的抗議,而是真正建立平台。

他們認為想要站穩,需要雙腳的配合,因此需要抵抗,也需要進步。從跳脫傳統的框架與限制開始,他們決定放手一搏,直接嘗試再說。當初最大的挑戰是如何籌措資金來維繫合作社的運作。至於實際上如何運作,希望創建一個「主客皆適用」的模型,為整個社區帶來正面的影響。像其他平台,FAIR BNB會收取百分之十五的費用,一半用於支持合作社的運作,另一半由客人用來資助當地的社會項目。因此,房東與客人支付同樣比例,同時對整個社區也有利。

Coop Cycle —— 運輸合作社/外送平台

Coop Cycle 創立於歐洲,目的是要創立真正屬於當地勞工的單車外送公司,像是在波爾多的這家公司。另外也有像 Mensakas 這樣的公司,所以 Coop Cycle 是好幾家公司一起組成的。透過各地不斷團結的力量,加強基層活動。截自2019年,歐洲共有 26 家這樣的合作社,也就是大概 100 個外送員,120 萬歐元營業額,也取得很多補助款,所以證明這些組織是可以在地化的。

Coop Cycle 透過建立網絡,一起募集資源。這並不是當地組織和資本主義平台之間的對立,而是要建立有意義、具全球規模,但仍然和基層緊密連結的組織。他們創立了集中式服務,分享平台技術,有些合作社還不太有名,但是我們把大家都集中起來,這樣使用者就可以在這個數位平台找到他們需要的服務。

合約和薪資管理也很重要。員工是所有服務的核心,所以不管他們在哪一個國家,都必須受到全面保障。所以我們必須知道如何利用歐洲各國的法律,來保障每一位員工。再來,還有一項技術層面也和外送業高度相關,那就是商業合作。例如:大量購買、支持新的合作社成立、發起倡議…等等。所以這張投影片主要想講的就是,當規模擴大到整個歐洲,的確會帶來一定程度的影響力。

Coop Cycle 在發展中也面臨許多挑戰,首先是建立永續且民主的商業模式,而且是從一開始就如此,並且在規模持續大時也要維持如此。老實說,要讓商業模式保持永續且民主,的確是項挑戰。再來,如何找到資金。他們當時發起了會員費的想法,每個在地合作社都有投資經費,不過問題是很多組織才剛成立,沒有足夠經費。所以後來申請兩次補助,也成功獲得。因為至少在歐洲,有滿多政治夥伴覺得這件事情是個社會議題,不過補助並不是持續不斷的。

另一個重要的議題是,如何給員工一個有生產力的工作環境,尤其是負責不同專案規模的員工,也還是一項挑戰。最後,如何防止資本主義平台吞食你的專案。開源數位平台要怎麼對抗資本主義企業?在希望平台是透明下且所有人可使用狀況下,要怎麼避免它被誤用?解決方法,是一種許可證,有這個許可證後,平台還是開放的,但是它的商業用途,僅限社會企業合作社成員使用,在如何保護公共財上,Coop Cycle 也做了非常多的努力。

土耳其 NeedsMap (İhtiyaç Haritası)需求媒合地圖平台

Needsmap在各個利益相關者的參與下制定了2020年主要戰略計劃:人道主義援助,應對技術,經濟復甦。NeedsMap 這個平台是基於實際物資傳遞的數據媒合地圖,將有需要的人和想要幫助的人聚集在一起。它滿足個人的基本需求(如衣鞋、外套和毯子),以及非政府組織,公立學校,合作社,志願團體,社交平台和社區中心(例如義工、學童文具、書籍,甚至油漆,計算機,投影機、辦公家具的共享與捐贈)。

主要創辦人之一 Ali ErcanÖzgür 在他的職業生涯中,致力於研究社會經濟地圖和數據驅動地圖,透過觀察基於鄰域的地理數據映射如何對決策者特別是在地方政府中發揮重要作用。 2012年,他建立了一個名為 City Kid 的網絡平台,該平台通過照片和視頻記錄了城市居民的問題,並使使用者可以直接與地方當局分享這些問題。 2015年,一群人開始考慮使用基於網絡的應用程序來解決基於地圖的數位系統,該應用程序可以解決城市和社區級的社會發展需求。

土耳其著名演員,聯合國開發計劃署土耳其可持續發展目標親善大使梅爾特·費拉特(MertFırat)也於發展過程參與其中,同意透過建立一個「社會合作社」,以基於網絡平台滿足共同的需求。他們認為合作社是最合適的機構形式,反映了圍繞團結和互助的價值觀。 2015年10月,在聯合國開發計劃署社會公益峰會上發布了NeedsMap(測試版)的beta版本,並逐漸發展為至今的形式。

這是人們自發參與的網絡平台,通過非貨幣捐款系統解決與貧困有關的社會問題。目前 NeedsMap 主要服務地區在土耳其,主要 7 個合作夥伴,服務超過 95,000 個用戶,雇用 7 位正式員工,迄今為止募集的資金超過 512,000 美元。

除了組成董事會和審計委員會的七個創始成員外,我們還有四個成員分別負責其不同部門(財務、義工、網絡平台、公私部門關係經營,專案計畫、公共關係和交易運營)。建立平台合作社使我們能夠共同解決社區問題,共同分享決策和責任。

對 NeedsMap 來說,在循環經濟中成為一個有效且用戶友好的社交平台至關重要。他們沒有任何倉庫或商店但是有一個基於志願者的合作平台,該平台可以滿足成千上萬的需求, NeedsMap有10,000名志願者,他們在野外,辦公室,大學以及數位環境中工作。

結語

台北在2020 IMD 全球城市智慧城市評比中排名第8,比前一年下降一個名次,但我們的都市真的更智慧了嗎?或是這種智慧只是屬於少數資本公司作為投資排名的參考數值?當城市因為網絡數位技術競爭,變得越來越平的同時,如何重新定位發展策略?

除了經濟導向的都市規劃,發展對「平台經濟」發展更友善的城市資源(科學園區、交通建設、產學發展等),都市自身對於數據的應用與技術的發展,與如何推動「公共價值倫理」為基礎發展?都市在面對跨國平台資本公司的進擊,是否總是要到問題發生,才能因應提出解決策略,或是我們能提早一步,主動捍衛都市數據作為公共基礎設施,並鼓勵更多由公民自主發起的合作平台經濟策略。

[1]Apple 和 Google 合作開發新冠肺炎接觸史追蹤技術 2020/04/10

[2]馬斯克用三隻小豬演示Neuralink生化腦技術,披露腦機界面最新成果,2020/08/31,數位時代

[3]優步化(Uberization)描述新參與者使用計算平台(例如移動應用程序)將現有的基於服務的行業商品化,以便聚合服務的客戶和提供者之間的交易,所謂的「平台經濟」通常指的是用避開了現存中介機構。與傳統業務相比,此業務模型具有不同的運營成本。

[4]City as a Growth Platform: Responses of the Cities of Helsinki Metropolitan Area to Global Digital Economy,2020,Urban Sc,Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko ,OrcID, Markus Laine and Henrik Lönnqvist]

[5]《贏家全拿:史上最划算的交易,以慈善奪取世界的假面菁英》,聯經,阿南德‧葛德哈拉德斯

[6]The Future of Humanity and the World of Technology — Society 5.0

[7]City as a Growth Platform: Responses of the Cities of Helsinki Metropolitan Area to Global Digital Economy,2020,Urban Sc,Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko ,OrcID, Markus Laine and Henrik Lönnqvist]

[8]什麼是平台合作主義(platform coop)?平台合作社的廣泛定義:「平台合作社是使用數字平台的共同所有,民主管理的企業,通過使人員和資產聯網,使人們能夠滿足他們的需求或解決問題。」界定範圍:

1.平台合作社受到技術社區內部開源運動的啟發,但它們沒有定義。平台合作社通常會採取開放式的方法,但是由他們堅持合作而不是開放的原則來定義。2.儘管它們不僅僅是增加參與度或改善治理的數字工具,但這些工具可能構成支持其民主性質的任何平台的一部分。3.工作條件和勞工權利是圍繞平台合作社的想法的核心,但它們卻也可能與其他利益相關者(當然包括用戶)相關。4.他們不僅僅是使用數位渠道/提供數位服務的合作社。有一個數位合作社的重要且受歡迎的領域,通常使用工人合作社模型,但是這比線上運營的平台合作社更集中的領域更廣泛,人們聚集在一起的平台,平台在其中推動業務和創建重要的依賴關係。

Referance: Digital democracy? Options for the International Cooperative Alliance to advance Platform Coops,ICA.

Fairbnb.coop launches, offering help for social projects

[Needs Map – İhtiyaç Haritası GLOBAL,INNOVATION EXCHANGE] (https://www.globalinnovationexchange.org/innovation/needs-map-ihtiyac-haritasi)

[The Future of Humanity and the World of Technology — Society 5.0] (https://medium.datadriveninvestor.com/the-future-of-humanity-and-the-world-of-technology-society-5-0-6e4dd5952bae)