Making process of City Mandala

Medium: Woodcut printmaking, AI-assisted image development, participatory workshop Venue: New Taipei City Museum of Art Year: 2024–2025 (commissioned, 1-year production) Extended process documentation: miro.com/app/board/uXjVLg2oSqI

Overview

City Mandala investigates collective memory, urban displacement, and cultural belonging in the Wenzaizun community — an urban village facing state-led demolition in New Taipei City. The project moves from ethnographic fieldwork to AI-assisted visual development to woodcut printmaking, treating each stage as a translation rather than a shortcut: research becomes prompts, prompts become visual options, options become carved wood, and carved wood becomes a participatory space.

AI was used in two distinct roles: as an image-generation tool for developing the visual language of the prints, and as a facilitation tool for structuring the participatory workshop programme.

Process

01 — Research Foundation

Thematic investigation drawing on urban studies, budget planning, and in-depth interviews with Wenzaizun residents, community workers, and local historians. This fieldwork produced the conceptual vocabulary — the specific textures, tensions, and imagery of a community under threat — that would be fed into both the visual and workshop development stages.

Research references included: Invisible Women (Caroline Criado Perez), The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Jane Jacobs), Invisible Cities (Italo Calvino), Spaces of Capital (David Harvey).

02 — AI as Visual Translation Layer

Building on prior training in AI image workshops, I translated the research materials into structured prompts. Writing prompts was itself a research act: testing which words, cultural references, and visual registers could carry the weight of collective memory without flattening it.

I ran experiments across multiple AI image-generation tools, producing ten visual variations — evaluating each against the project’s conceptual demands rather than surface aesthetics.

PROMPT 01 — Testing “Mandala Structure × Activist Printmaking”

A mandala-structured woodcut print inspired by Asian activist printmaking collectives. Bold black-and-white contrast, dense composition. Center: symbols of a just city — scales of justice, green rooftops, public squares with citizens. Outer rings: workers, farmers, artists holding natural elements as tools of resistance. Outermost: demolition cranes, luxury towers, bureaucrats over maps. Style references: Taring Padi Indonesia, A3BC Japan, high-contrast linocut, street poster aesthetic.

Tool: Dreamlike.art Testing: Can a mandala structure hold activist visual language? Result: Composition worked but style became too decorative — lost the rawness of printmaking → excluded

Prompt 02 — Testing “Organic City × Local Ecology” [SELECTED]

Woodcut-style illustration of an urban community map with fisheye perspective. Streets and houses surrounded by rivers and mountains. Flowers growing from road ends — bougainvillea, iris, camellia, hydrangea — each branch containing a small human figure at its center. Ladybirds, fireflies, dragonflies woven through the flora. Cell-like irregular outer boundary. Black ink on cream paper, activist printmaking aesthetic, dense organic detail.

Tool: Dreamlike.art Testing: Can the specific species documented in fieldwork become visual protagonists? Result: Strong ecological grounding, human figures at natural scale → entered final direction

PROMPT 03 — Testing “Workshop Participants’ Urban Imagination” [SELECTED, modified]

Woodcut print collage of 23 urban scenes from a community in Taiwan. Scenes include: cats and night-herons sharing a sidewalk, guerrilla theatre under a viaduct, street-side opera performance, shared bookshelves on a pavement, elderly residents in a theatre troupe, a night market stall, factory workers’ daily life. Each scene framed in irregular organic cells. Black-and-white high-contrast, community printmaking style, intimate and documentary.

Tool: Dreamlike.art Testing: Can the 23 scenes from workshop discussions translate into a single visual system? Result: Scene density too high, details fragmented → adjusted to layered presentation → modified and adopted

The goal was not to find the most beautiful image — but to find the direction that could hold the complexity of what I heard and saw in the field.

04 — AI as Workshop Facilitation Tool

In designing the participatory workshops, AI was used to synthesise and structure the large volume of field material, resident interviews, and thematic threads into coherent discussion frameworks. The three core workshop questions were developed through this process:

- What matters to you in [home / street / community] scales?

- What do you think is the greatest value among the people and things you care about most?

- Following the above discussion, what recommendations can we offer to urban planners across different scales?

The workshop discussion guides were organised around two creative directions distilled from fieldwork: bottom-up urban planning and feminist spatial thinking. Using AI to synthesise months of field material meant the workshops could be designed around what residents actually said, rather than importing a generic participatory format.

05 — From Screen to Wood

The selected AI-generated direction became a reference layer — not a final image, but a visual grammar — which I interpreted and extended through hand-drawing and woodcut carving. The physical resistance of the wood, and the irreversibility of each cut, introduced a material weight that the digital image could not carry.

Production process: carving → proofing → final printing → exhibition material production and transport coordination.

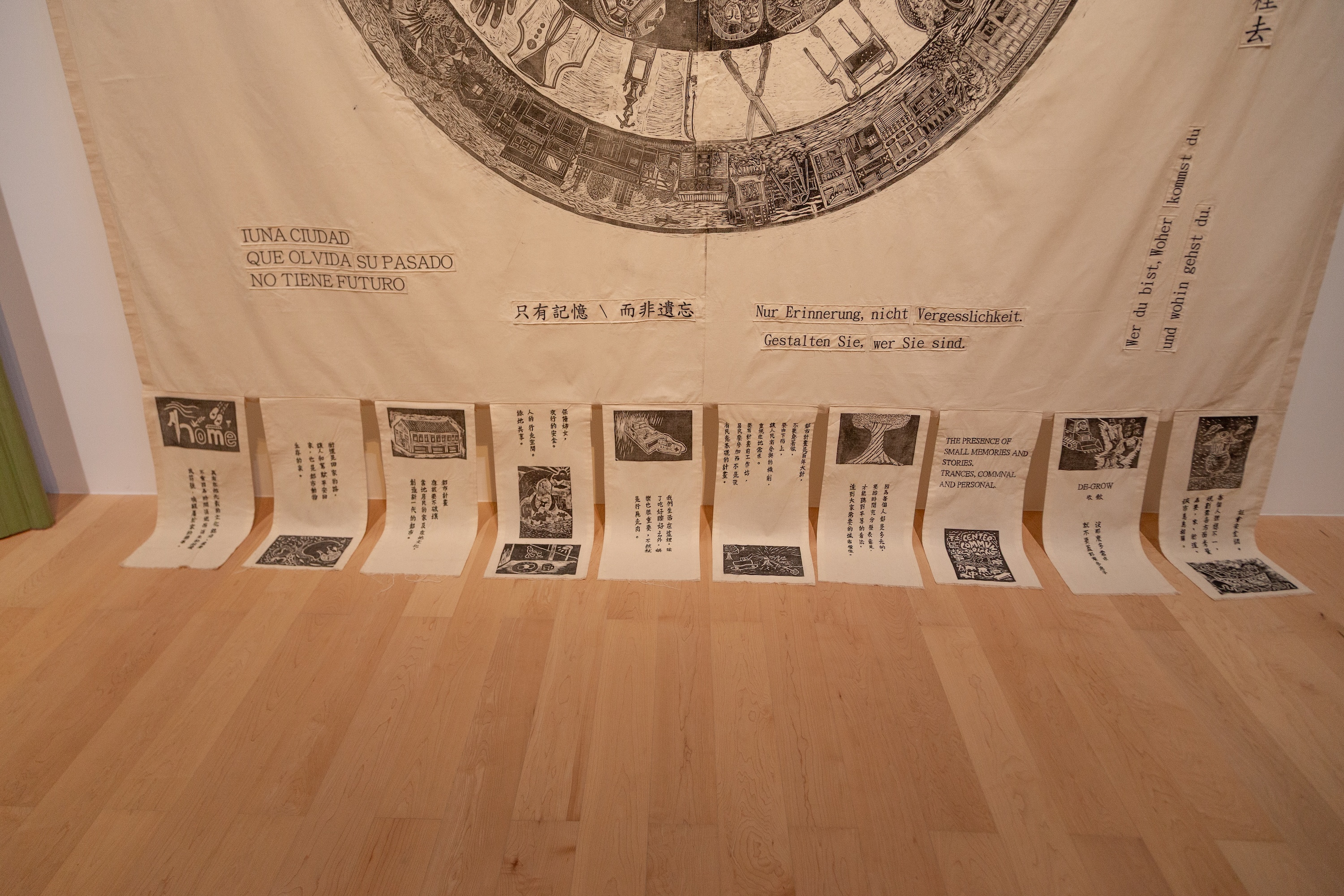

06 — Exhibition & Public Workshop Programme

Exhibition spatial planning included scale model production for display testing and logistics coordination with the museum.

During the exhibition period, participatory workshops were co-designed and facilitated with residents. The AI-structured discussion framework was deployed here — allowing conversations to be anchored in the specific concerns of Wenzaizun while remaining open to participants’ own urban experiences. The workshops extended the work into collective creation, transforming the exhibition from a site of viewing into a shared space of dialogue and action.

What AI Made Possible

In image development: Generating and evaluating ten visual directions at speed allowed me to test how research material translates into image — which words activated the right visual registers, which were too literal, which produced unexpected but generative results. The variations became a decision-making tool, not a destination.

In workshop design: Using AI to synthesise months of field material meant the workshops could be designed around what residents actually said, rather than generic participatory frameworks. It compressed the gap between fieldwork and facilitation.

In both cases, AI expanded my capacity to hold complexity — not to simplify it.

About Wenzaizun

Once a wetland transformed by early migrants, Wenzaizun evolved into a hub of informal housing construction in the 1970s and has since become a symbol of Taiwan’s post-industrial urbanisation. Amid long-standing disputes over urban planning, the area has gradually entered the final stages of state-led demolition. The daily movements, internal narratives, and emotional bonds of its residents risk being erased alongside the buildings.